Secret Scanning with Aho-Corasick

Secret Scanning with Aho-Corasick

Most people assume secret scanning is just “grep, but bigger.” That intuition is understandable, and dangerously incomplete for systems where leaked secrets are permanent.

Real-world secret scanning means inspecting millions of files for thousands of secret formats at once. These include API keys, OAuth tokens, private keys, database credentials, wallet private keys, seed phrases, and smart contract deployment credentials. Nearly all of these formats can be expressed as regular expressions. Applying those expressions naively does not scale, even when the underlying regex engine is fast.

This article explains why the obvious approach fails, what actually works in practice, and why systems with irreversible credentials demand more rigorous scanning than traditional infrastructure.

The intuition trap

Regular expressions are powerful and familiar, which makes them dangerous in large systems. Most regex engines scan input left to right and attempt patterns one at a time. When a partial match fails, the engine backtracks and retries alternative paths. This often means rereading the same characters multiple times.

That cost is usually acceptable when inputs are small and patterns are few. Secret scanning violates those assumptions simultaneously. Source files can contain extremely long lines, such as minified assets, generated Solidity artifacts, or hardhat compilation outputs. Mature scanners maintain hundreds of detection rules. GitHub scans repositories for known types of secrets, using patterns and heuristics to identify sensitive data. Large organizations scan entire repositories, commit histories, contract deployment scripts, and artifact stores.

In that environment, backtracking behavior compounds. Runtime becomes unpredictable, CPU cache efficiency degrades, and memory pressure increases. Systems fail when they cannot finish, regardless of correctness.

Treating scanning as a systems problem

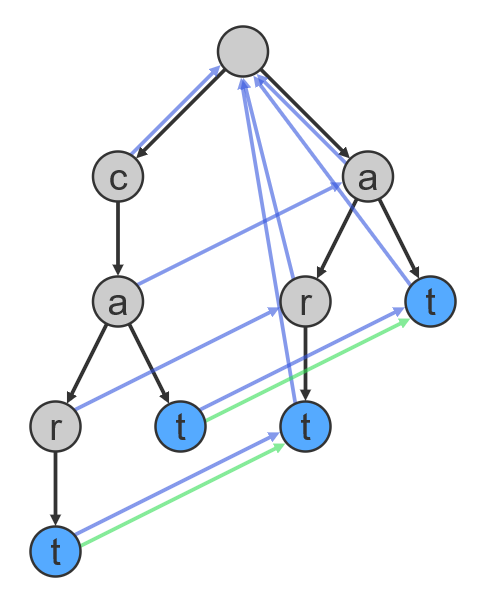

Aho-Corasick is a string-searching algorithm invented by Alfred V. Aho and Margaret J. Corasick in 1975 that locates elements of a finite set of strings within an input text by matching all strings simultaneously. Instead of checking patterns sequentially, it builds a trie that contains all patterns at once. Each node represents a prefix shared by one or more patterns.

Failure links connect shared suffixes:

- When scanning “cat”, if next char isn’t ‘r’, jump to state “at”

- When scanning “cart”, if match fails, jump to state “art”

Example Aho-Corasick Trie for patterns: “cat”, “at”, “cart”, “art”.1

The critical addition is the construction of failure links. These links point to the longest valid suffix that is still meaningful when a match fails. When the scanner encounters a character that does not continue the current match, it transitions along a failure link to the next viable state rather than restarting from the beginning.

The scanner effectively asks: given everything seen so far, what prefix still makes sense? Each input character is processed once, in constant time. The complexity of the algorithm is linear in the length of the strings plus the length of the searched text plus the number of output matches.

Performance Comparison: Regex vs Aho-Corasick

Time Complexity Analysis:

Naive Regex Approach:

- For P patterns and input of length N

- Worst case: O(P × N × M) where M is pattern length

- Backtracking can cause exponential blowup

Aho-Corasick Approach:

- Construction: O(total pattern length)

- Matching: O(N + matches)

- Independent of pattern count

This predictability matters more than raw speed. In large systems, runtime predictability allows scanning to be continuous. For teams managing irreversible credentials, continuous scanning prevents keys from reaching public infrastructure.

The hard limitation and the challenge of unstructured secrets

Aho-Corasick only works on fixed strings. Secret formats are not fixed strings. They include variable-length components, encodings, and provider-specific structure that require regular expressions to validate.

This limitation is especially problematic for cryptographic secrets. While cloud providers increasingly use structured prefixes (AWS with AKIA, GitHub with ghp_), raw private keys are just 64 hexadecimal characters. Seed phrases are 12 or 24 common English words with no identifying prefix. Private keys can be base58-encoded byte arrays. None of these formats announce themselves.

Secret Format Examples

Prefixed (Aho-Corasick friendly):

✓ AWS Access Key: AKIAIOSFODNN7EXAMPLE

✓ GitHub Token: ghp_16C7e42F292c6912E7710c838347Ae178B4a

✓ Stripe API Key: sk_live_4eC39HqLyjWDarjtT1zdp7dc

Unprefixed (requires entropy analysis):

✗ Private Key: b3f4c7a9e8d2f1a6c5e9d8b7a4f3e2c1d9b8a7f6e5d4c3b2a1

✗ Seed Phrase: abandon ability able about above absent absorb abstract absurd abuse access

✗ Base58 Key: 5HueCGU8rMjxEXxiPuD5BDku4MkFqeZyd4dZ1jvhTVqvbTLvyTJ

Why secret prefixes exist (and when they don’t)

Secret prefixes were not designed to help security scanners. They emerged from operational needs. AWS introduced structured key prefixes in the early 2000s to enable routing, partitioning, and lifecycle management at scale. Human readability and detectability were side effects.

Over time, prefixes became common across providers because they reduce ambiguity and improve debuggability. More recently, Microsoft formalized this idea through the CASK (Cryptographically Attestable Secret Keys) standard, which proposes a shared format for security credentials designed to be easily identifiable by automated tools.

The premise behind CASK is simple: secrets that cannot be reliably identified at rest will be leaked longer and remediated later.

For scanners, prefixes convert an intractable matching problem into a staged detection pipeline. But cryptographic protocols were designed before this pattern became standard. Raw private keys predate the security scanning era. This creates a detection gap that cannot be solved with Aho-Corasick alone.

The entropy and context problem

Scanners for unstructured secrets must layer additional detection methods. High-entropy string detection catches sequences that are statistically unlikely to be natural language or structured code. A 64-character hex string has entropy that stands out. Twelve random dictionary words in sequence are statistically improbable.

TruffleHog employs complex patterns and entropy analysis to detect hard-coded secrets like API keys, cryptographic keys, and passwords that might be inadvertently exposed.

But entropy-based detection produces false positives. Hashes, UUIDs, test vectors, and cryptographic examples all look like secrets. Context analysis helps: a hex string assigned to a variable named PRIVATE_KEY or DEPLOYER_SECRET is more suspicious than one in a test fixture. A 24-word phrase preceded by a comment saying “example mnemonic” might be safe.

Entropy-Based Detection Example

def calculate_shannon_entropy(data):

"""Calculate Shannon entropy to detect high-entropy strings"""

if not data:

return 0

entropy = 0

for x in range(256):

p_x = float(data.count(chr(x))) / len(data)

if p_x > 0:

entropy += - p_x * math.log2(p_x)

return entropy

# Typical entropy thresholds:

# - Natural language: 3.5-4.5 bits/char

# - Base64 encoded data: 6.0 bits/char

# - Truly random data: 8.0 bits/char

# Example:

entropy("hello world") # ~3.18 (low - likely not a secret)

entropy("AKIAIOSFODNN") # ~3.57 (medium)

entropy("b3f4c7a9e8d2") # ~3.58 (high - potential secret)

This staged approach—Aho-Corasick for prefixed secrets, entropy analysis for raw keys, context validation for ambiguous cases—makes modern scanners viable. None of these methods is sufficient alone.

Why this matters operationally

At scale, the bottleneck in secret scanning is finding candidate matches across massive inputs without drowning in false positives or missing true leaks.

A system that applies hundreds of regexes to every line, scans all file types indiscriminately, and processes unbounded line lengths will eventually fail under load. When that happens, coverage is reduced, scans are slowed, or alerts are dropped. For projects managing irreversible credentials, a missed scan is an operational failure and a potential exploit vector.

Scalability Comparison

Scanning 10GB repository with 1000 secret patterns:

Naive Sequential Regex:

├─ Pattern 1 → Full scan: 2.3s

├─ Pattern 2 → Full scan: 2.1s

├─ Pattern 3 → Full scan: 2.4s

└─ ... (997 more patterns)

Total: ~35 minutes

Aho-Corasick Pipeline:

├─ Build trie: 0.05s

├─ Single pass scan: 4.2s

├─ Entropy analysis on candidates: 0.8s

└─ Regex validation: 1.1s

Total: ~6 seconds

Speedup: 350x

A prefix-based approach changes the economics. Runtime scales with input size rather than pattern count. CPU cache behavior improves. Memory growth becomes predictable. False positives are filtered only after cheap detection has already narrowed the search space.

This distinction determines whether a scanner can run continuously or only in controlled environments. For development teams managing irreversible credentials, continuous scanning must include pre-commit hooks that prevent secrets from ever entering version control, because retrospective detection is too late.

What real secret scanning looks like

In practice, scalable scanners use a tiered pipeline:

Stage 1: Fast Aho-Corasick pass for known prefixes (API keys, service credentials, some wallet formats)

Stage 2: Entropy analysis on high-entropy strings (raw private keys, encoded seeds)

Stage 3: Context validation using variable names, comments, file paths

Stage 4: Format-specific validation (checksum verification for addresses, signature testing for keys)

Stage 5: Provider confirmation APIs where available (check if key is active)

GitHub secret scanning scans entire Git history on all branches for secrets, and periodically runs full Git history scans for new secret types when new supported patterns are added. Most inputs never reach the expensive stages. This architecture survives real workloads in systems like GitHub secret scanning, GitGuardian, and tools such as TruffleHog.

Pre-commit hooks: the first line of defense

For projects managing irreversible credentials, repository scanning alone is insufficient. By the time a secret reaches your main branch, it may have already synced to developer forks, CI/CD logs, or external systems if automated deployment ran.

Pre-commit hooks run scanning before changes enter version control. Tools like Husky, pre-commit, or Lefthook can invoke lightweight scanners that check staged changes in milliseconds. This prevents secrets from ever entering Git history, which is the only reliable prevention for irreversible credentials.

The tradeoff is developer friction. Hooks that are too slow or produce false positives will be bypassed. This is why the scanning performance characteristics matter—a hook that takes 5 seconds per commit will be disabled; one that takes 50 milliseconds will be tolerated.

Practical constraints that matter

Even with Aho-Corasick, production systems impose limits. They restrict scanning to file types that commonly contain secrets. They cap line length to avoid spending resources on autogenerated artifacts. They limit character sets because most secrets resemble base64 or hexadecimal strings.

For projects with sensitive credentials, additional constraints help. Exclude known test mnemonics (like the standard Hardhat test seed phrase). Skip dependency lock files and node_modules. Ignore data exports and transaction dumps that contain addresses without private keys.

These constraints make scanning feasible without overwhelming human reviewers.

How to evaluate a secret scanning tool

You do not need to read the source code to ask useful questions:

- Does runtime grow predictably as repositories get larger?

- Can the scanner run continuously without timeouts?

- Does it detect raw private keys and seed phrases, not just prefixed API keys?

- Can it run as a pre-commit hook without breaking developer workflow?

- Does it reduce false positives before human review?

- Can it explain why a secret was detected?

- Does it integrate with your deployment pipeline to prevent automated pushes with leaked keys?

GitHub supports validation for pair-matched access keys and key IDs, with validity checks showing whether a secret is active or inactive. Tools that cannot answer these questions tend to move cost downstream, through alert fatigue, manual triage, and delayed response. For systems managing irreversible credentials, delayed response often means the damage is already done.

The cost of failure

Traditional secret leaks are expensive. Leaks of irreversible credentials can be catastrophic. A leaked private key to a multi-signature treasury wallet, contract deployer account, or protocol admin address enables irreversible theft or manipulation. The leaked key cannot be rotated—systems must be redeployed, assets migrated, and users convinced to switch, all while attackers have the same access you do.

Secret scanning must ensure that the one secret that matters most never touches a repository, a log file, or a screenshot.

Closing

Secret scanning is a systems design problem under adversarial and operational constraints. For systems managing irreversible credentials, those constraints are stricter and the consequences more severe.

Aho-Corasick provides linear-time pattern matching as the foundation. Combined with entropy analysis, context validation, format-specific checks, and pre-commit enforcement, it enables predictable behavior at scale with acceptable false positive rates.

That predictability determines whether a scanner actually reduces risk in the real world. For projects where leaked secrets are permanent, the stakes demand continuous, reliable, and comprehensive scanning.

Want to see these principles in action? Check out Yeeth’s implementation of pre-commit secret scanning for the Eclipse Foundation’s OpenVSX registry: github.com/eclipse/openvsx/pull/1510/files. The implementation shows how to integrate lightweight scanning into real development workflows without breaking developer experience. Comments and feedback welcome.

Footnotes

1. Generated using Aho-Corasick String Matching Algorithm Visualizer. ↩

References

- Aho, A. V., & Corasick, M. J. (1975). Efficient string matching: An aid to bibliographic search. Communications of the ACM, 18(6), 333-340.

- GitHub Docs. (2024). About secret scanning. https://docs.github.com/code-security/secret-scanning

- TruffleHog. (2024). Find, verify, and analyze leaked credentials. https://github.com/trufflesecurity/trufflehog

Yeeth Security writes about building security systems that work under real constraints rather than idealized assumptions.

https://blog.yeeth.xyz

https://yeeth.xyz